Note that this manoeuvre is no longer included in the driving test (since 4 December 2017). However, in the real world it is still important, because sooner or later you’re going to have to do it when you’re driving on your own.

This article gets a lot of hits, and reversing around a corner is the manoeuvre many of my own pupils struggle with the most.

What seems to make it so difficult is that you have to control the car all the way through – it’s not just full lock one way, then full lock the other – so you need to know which way to turn the wheel. And that’s where the problems arise: steering the car when it is going backwards. In my experience, most people – 80% or more – seem have problems initially, and for some it is always a real struggle.

The secret to overcoming the issue of which way to steer and mastering the manoeuvre is to retrain your instinctive behaviour by careful calculation. What does that mean?

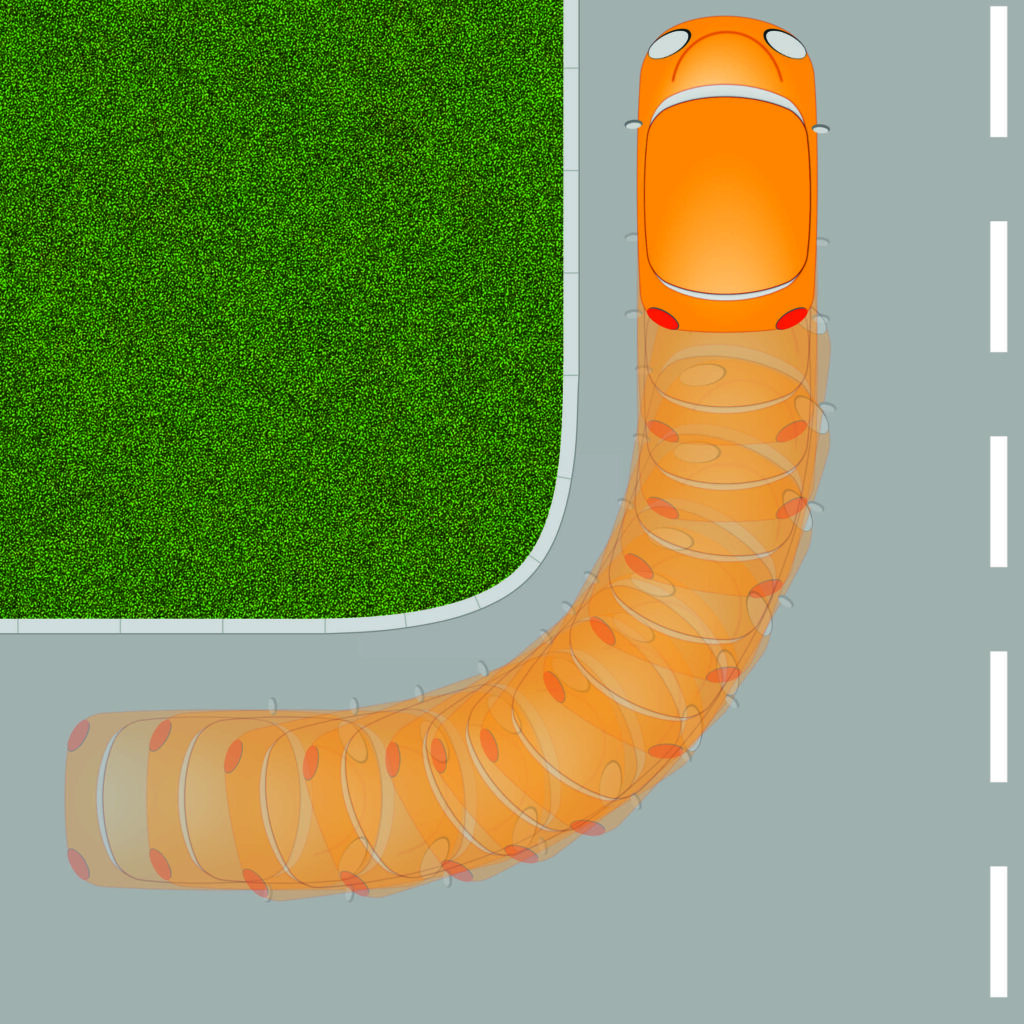

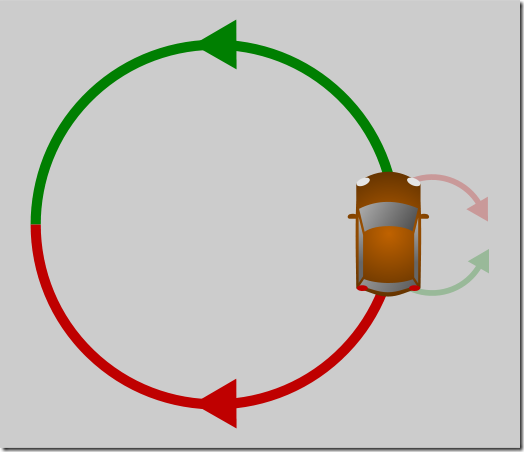

Well, imagine you are sitting in your car in the middle of a big, empty car park. If you steer left and drive forwards, as shown by the green arrow in the diagram, then obviously the car will turn to the left. What you might not be aware of is that the back of the car swings out to the right, but since you aren’t usually looking at that bit of your vehicle when you’re driving your brain doesn’t take it into consideration.

However, if you stop, put the car into reverse, and then start to move backwards, although the car will still turn to the left, as shown by the red arrow, this time the front of the car swings out to the right. You see that quite easily, and when you’re stressed your brain will instinctively try to make sense of that. Your instincts kick in and immediately tell you to steer the opposite way.

Your instincts can get even more confused by information provided by the mirrors. It is surprising how many people without previous experience subconsciously believe that everything in the mirrors is the opposite way round, and since your instincts feed off your subconscious, relying on them can be a recipe for disaster.

Remember that your instincts will kick in whenever you are stressed, and if they’re incorrectly programmed you’ll usually end up steering the wrong way when reversing around a corner. The secret is to: take your time, stop… and think… often.

Each time you stop, you must work out – calculate – what to do based on the hard facts, as illustrated in the above diagram. Ignore the front of the car as you do your calculation – you’re guiding the rear end. Absolutely the worst thing you can do, and especially so when you are still learning, is to go quickly and avoid stopping, because that forces your instincts to take over. The more you get it right, the more confident you will become, the less stressed you will be, and the quicker your instincts will get retrained.

Reversing around a corner is actually quite simple, and on your test all you’re expected to do is keep reasonably close to the kerb and watch out for other road users (the examiner only has tick boxes for “control” and “safety”). The examiner won’t get out and use a tape measure, and as long as you don’t mount the pavement or end up across the other side of the road then you’re unlikely to attract even a driver fault, let alone fail your test. The examiner doesn’t care what method you use, or how often you stop (as long as you don’t take forever and cause hold ups for other road users), so you can gauge your position relative to the kerb by looking out of the back window, the rear passenger window, using your mirrors, or a combination of any of these. You can steer as much or as little as you like as long as you remain in control – and are aware of what is happening around you.

Remember that reversing into a corner isn’t a parking manoeuvre, and you shouldn’t attempt to get really close to the kerb. You want to try and keep about as far away from it as you would be if you were emerging to turn left going forwards.

Here’s a fool proof method which works every time. For it to work, your mirrors must be adjusted the same every time – if they aren’t, your position relative to the kerb will be different.

First of all, look at the bottom edge of the mirror housing in the picture above. Note the two white dots – I have marked these on the picture using my graphics software, but you can put suitable markers on your own car using Tipp-Ex (which you can scrape off easily without leaving any marks) or two rubber bands. The actual positioning of the dots isn’t critical – all you need to do is split the mirror approximately into thirds. You don’t even need to put any marks on your car – just imagine the position of the thirds markers.

Step 1

Drive past the road you want to reverse into and stop safely about two to three car lengths beyond it, and about half a metre (the width of a drain grating) from the kerb. When you look in the mirror you should see that the kerb is more or less at the nearest third marker (as shown in the picture above). It doesn’t matter if it’s a bit closer or a bit further – as long as you can see it.

Step 2

Get the car into reverse, and safely and slowly reverse back until the kerb curves away from the car, as shown above. Stop when it lines up with the furthest third marker. This is the point of turn (where the kerb is branching away from the car).

Step 3

This next part is critical: work out which way you need to steer. The kerb has moved away from you(←, or “to the left”), so you need to steer towards it (←, or also “to the left”). Steer one complete turn of the steering wheel in that direction.

Step 4

Reverse safely and slowly until the kerb comes back to the nearest marker.

Step 5

This part is critical again: work out which way you need to steer. The kerb has moved towards you (→, or “to the right”), so you need to steer away from it (→, or also “to the right”). Steer one complete turn of the steering wheel in that direction.

The kerb will now move away from you again. Repeat the above steps – carefully working out which way to steer every time you stop – until the car is into the side road.

Step 6

Once you are parallel with the kerb in the side road, stop. This part is critical again: work out which way you need to steer. If you continue moving without doing anything, you will continue to get closer to the kerb and will hit it – so you must steer away from it (→, or “to the right”) to avoid that. Steer one complete turn of the steering wheel in that direction.

Step 7

Reverse back safely in a straight line for about 3-4 car lengths, then stop and secure the car.

You do not have to use the handbrake each time you stop as you move around the corner (but it doesn’t matter if you do). Use it if it will help prevent the car from rolling, and especially if you’re reversing on a slope.

I can’t emphasise strongly enough how important it is to stop and work out which way you need to steer. If you react on instinct you will almost certainly steer the wrong way, so you have to calm things right down and prevent instinct from taking over.

One useful tip is to talk out loud. If I stop my pupil and ask “which way has the kerb gone?” they should answer “away from me” (if that’s the case). I will then ask “so what do we want to do?” and they will say “get closer to it”. I then ask “so which way should we steer?” – and this is where logic must beat instinct: logically, if the kerb has moved away, and we want to get closer, we simply steer towards it. If the pupil can do that with me asking the questions, they should be able to do it if they ask the questions themselves – except that if they only think the questions instead of saying them out loud, the subconscious is involved and instinct is likely to win out. By asking the questions out loud, the conscious is involved, and logical actions are much more likely.

Are there any other ways to do it?

Of course. As long as you can get round the corner safely and in control, you can do it however you want. If you have good reverse steering skills there is no reason why you can’t just go slowly and steadily round the corner, steering as much or as little as you need until you’re in the side road. Actually, that’s the ideal way of doing it – just don’t forget to keep an eye out for other traffic and pedestrians, which is easier said than done when you’re still moving and trying to avoid the kerb. Depending on the car you’re using, you could watch the kerb out of the rear passenger or quarter light window, or even out of the back window. However, do not be fooled into thinking you shouldn’t use your mirrors: they’re there for precisely this kind of thing.

Is there a fool-proof way of doing this manoeuvre?

The one I have described here is pretty close. As I said at the start, this manoeuvre requires you to control the car throughout based on your position relative to the kerb. I suspect that you’re asking this question with a view to finding a method where you don’t have to think: you’re not going to find one. Like it or not, you need to know what you are doing, and this method works for any wide corner.

Isn’t your method too prescriptive?

Other instructors love this sort of nit-picking. Many people have major problems steering in reverse, and it is not written anywhere that they must be able to go backwards around a corner at speed without stopping. New drivers need all the help they can get, and whilst they may one day be able to whizz safely and accurately around a corner whilst simultaneously solving a Rubik’s Cube and playing the banjo, during this phase of their life when they can’t do that, this method (or a similarly prescriptive one) can help them.

Why can’t they just steer round naturally?

The fact that you’re reading this ought to make the answer obvious! If your pupil (or you) can do it freestyle with their eyes shut, all well and good. If your pupil (or you) has problems knowing which way to steer, you would be stupid to persist with doing it freestyle – they/you will just get in a mess and steer the wrong way. It’s a waste of the pupil’s time and money, and highly detrimental to the instructor’s reputation if the pupil decides they’re not getting anywhere. Not “making progress” whilst haemorrhaging money is one of the big reasons I pick up partly-trained pupils who’ve had enough.

What do I do if another car turns up when I’m reversing?

You need to use your own judgement. As a rough guide, while you are on the main road, wait for anyone coming up from behind (don’t worry too much about those coming from the front unless it’s a very narrow road). Once you’re turning in, keep an eye on those approaching from the left/front but only worry about stopping to wait if it’s a narrow road or if they are turning into the side road). Once you are well into the side road, cars on the main road are not an issue as long as they’re not turning into the side road. At all times, be aware of traffic coming up behind you from the side road.

Of course, a lot will depend on where you do the manoeuvre. The Golden Rule is not to fail to see approaching traffic (or pedestrians) because the examiners are watching for precisely that. Generally, if you look, you will see – if you don’t look, you can’t see!

What do I do if someone flashes their lights at me?

Make sure that they’re flashing at you and not someone else, and then carry on with the manoeuvre if it’s clear that they’re waiting for you – but keep an eye on them, because once you’re around the corner (assuming they’re behind you) they’ll probably go past and you’ll have to pause as they do.

What would be a serious fault on this manoeuvre?

The decision will be the examiner’s, but as a rough guide: missing other cars and pedestrians, not looking all around before commencing the actual turn, mounting the pavement, going more than half way across the side road at any point in the manoeuvre, and so on are likely to be marked as serious faults.

Never self-assess, though. Most people who assume they have “failed” for something usually turn out to be wrong, and not long ago one of my own pupils rode up the kerb slightly and slipped back down again (jeopardising my alloys) and still passed. It depends on how good the drive was, and the way the particular examiner marks tests.

Do I fail if I stall when reversing around a corner?

No. Not automatically. It depends on various factors – how many times, how you deal with it, what is happening at the time (i.e. other road users), and so on. Aim not to stall, stay calm if you do, then concentrate on the rest of the test and keep your fingers crossed. Don’t self-assess. It’s the examiner’s decision, not yours.

Read the article on stalling.

At what point do I turn?

It doesn’t have to be millimetre perfect. All you’ve got to do is follow the kerb around, making sure it doesn’t go too wide or disappear into the side of the car when looking in the left mirror, and you’ve cracked it. Generally, you want to start turning just as the kerb starts to curve away from the car. The method I’ve detailed above takes care of it for you.

How much should I turn the wheel when reversing around a corner?

To go round most corners driving forwards you’ll need between a half and one full turn of the steering wheel. It would obviously need about the same amount going round it in reverse. It depends on the corner – some are much tighter than others – and the exact amount of steering will also depend on your car, since some have tighter turning circles than others. The method I’ve detailed above takes care of it for you.

What if it’s a very sharp corner?

Good question. The method I have detailed above will not work as it is written for sharp corners.

To deal with sharp corners, all you have to do is work out where the turning point is, then apply full lock. In my car (and when I’m driving), when the kerb of the road I’m reversing into appears just inside the nearside passenger window (see image above), that’s the turning point. You can work it out for your car (or seating position) by driving slowly forwards around the corner (i.e. doing the manoeuvre in reverse) and stopping as soon as you are straight. Take a look where the kerb of the target road is and remember that position.

If you’re trying to teach this to a pupil, remember that what you see in the side window will not be the same as what the pupil sees (unless they have their seat adjusted to exactly the same place you do, and they’re the same height as you). Let them work out their own reference point – don’t tell them what it is, because it probably won’t be!

Which way should I steer?

This is the main reason many learners have problems with this manoeuvre. Their instincts tell them to steer in exactly the opposite direction to what is required whenever they are reversing (I’ve explained the probable reason why, above). Instinct takes over whenever the pupil is panicked or rushed. Quite simply, you steer the way you want the car to move, whether driving forwards or backwards. The direction you steer does not change when you are reversing.

As I explained above, talking to yourself can help a lot – it forces you to work things out instead of just going on instinct.

Can I dry steer?

Yes, if you need to. Dry steering is when you steer while the car is stationary, and although it isn’t good practice to do it unnecessarily (it can damage the tyres, the steering column, and the road surface), it is NOT marked on the test. You can read more about steering in this article. In any case, you will usually only be steering a little while you are carrying out this manoeuvre, so dry steering is even less of an issue.

Should I use the handbrake every time I stop?

No. Use it if there is a risk of rolling, if you think you might be waiting for a long time, if you want to shift your foot, and so on. Otherwise, control the car smoothly using the brake and clutch as necessary (not at the same time, though). Having said that, if you do use the handbrake for each stop you’re not going to fail for it, so if it makes you feel better go ahead and use it (several years ago, one of my pupils was told on the debrief that there was no need to use the handbrake so much – but no fault was recorded and they still passed).

My last instructor told me it’s wrong to look in the mirrors

Your instructor is wrong, and you did well to get away from him before he did any more damage. The aim of this manoeuvre is to stay reasonably close to the kerb and to keep an eye out for other traffic. Your mirrors are there to tell you what is happening behind you, so you should make use of them. Just make sure you don’t stare at them – just as you shouldn’t stare out of the back window like a zombie if you’re using that method. Move your head and look around you, but don’t be afraid to use the mirrors as your primary way of gauging distance from the kerb.

But what if I can see the kerb out of the window?

Use that by all means. Just be aware that when you buy your own car you might not be able to see the kerb through the windows. I pick up loads of pupils who can’t use that method in my Ford Focus and they haven’t got a clue what to do. A mirror-based method works in any car.

What does the left wing mirror tell me?

It came as a big surprise to me when I discovered that a few pupils actually believe that if something is moving closer to them in the left mirror, it must be moving away from them in reality! This is not correct. If something is getting closer in the mirror, it is getting closer. Period.

Although it depends on how you’ve adjusted it, as a rough guide you want to keep the kerb about a third of the way across the left wing mirror.

Can I ask the examiner to adjust the mirror for me?

Yes. The examiners’ DT1 guide says that they should not refuse to assist if this request is made. Obviously, this only applies to manually-adjusted mirrors – you can adjust electric ones from the driver’s seat. As I said above, if your mirrors are in the correct place for normal driving then they don’t really need to be adjusted. However, I am aware that some ADIs advise their pupils to adjust the mirror downwards so that they can see the kerb, and although I personally cannot see the point, if that’s how you do it then it doesn’t matter if it works for you.

Do I need to adjust the mirror?

If it’s in the right place for normal driving, quite honestly you don’t need to. Some people do, though. It’s up to you.

I can’t adjust the mirror any more to see the kerb

If you are quite short, then you may find that the mirror won’t go much lower. As I said above, you don’t really need to move the mirror away from the normal driving position to see enough of the kerb to reverse around the corner. I know that some instructors do teach it with a lowered mirror, but you have just discovered one of the drawbacks to doing it that way.

How far away from the kerb should I be?

I teach my pupils that ½ metre (about a drain grating’s width) away from the kerb is perfect, ¾ metre is a little wide (but acceptable), and more than ¾ metre is too wide. These are the ratings I use on lessons – they do not apply to the driving test.

On the driving test the examiner’s decision is final, and in most cases they are happy as long as you don’t hit the kerb or go more than half way across the road you’re reversing into at any point during the manoeuvre. My approach to teaching the manoeuvre is that by training my learners to be very accurate about it, if they deviate a bit on their tests then they’ll still be well inside acceptable limits.

Will I fail if I’m too far away from the kerb when I’ve finished?

Yes. Probably. But “too far” is a grey area, and you have to be very wide indeed to fail for it. As I said above, as long as you are on your side of the road you shouldn’t really get more than a driver (minor) fault.

Remember that this is not a parking manoeuvre. You are not supposed to keep really close to the kerb (½ to ¾ of a metre is ideal). As a rough guide, you need to be about as far away from it as you would be if your were driving forwards to turn left.

What happens if I touch the kerb?

First of all, never self-assess your performance when you’re on your test. People who assume that they have failed because they’ve made a mistake are often wrong. Brushing the kerb isn’t an automatic fail (DT1, the examiners’ own internal reference document, says that). Some examiners seem to be harsher than others considering all the tales I hear, so it’s obviously best to not touch the kerb at all – but if you do, don’t worry about it and keep your fingers crossed.

Mounting the pavement is almost certainly a fail – but again, don’t assume anything! Not long ago one of my pupils rode up the kerb slightly and then slipped down again (risking taking chunks out of my alloys), but he still passed. He probably wouldn’t have if he’d have managed to get the whole wheel on to the pavement, but the point is that the rest of the drive can play a big part in how some mistakes are marked. Examiners often use common sense and aren’t out to fail people without a good reason.

Is it OK to keep stopping during the manoeuvre?

Yes, yes, yes, YES! Although it IS possible to fail for taking too long to complete the manoeuvre, stopping for a few seconds a half a dozen times as you steer around is not going to push it anywhere near this. The worst that can happen is that you’ll get a driver fault for taking a bit too long – which is much better than a serious fault for steering the wrong way and messing the whole thing up. Take your time. The problem with keeping moving while trying to figure out which way to steer is that the car will carry on going wider or closer, then you’ll panic and your badly-programmed instincts will tell you to steer the wrong way or by too much, then the whole thing is ruined. If you stop, the kerb stops getting closer or further away and you can think what to do.

It doesn’t matter how long it takes when you’re trying to master it on your lessons. Start out slow – a suitable speed will come naturally later.

My instructor told me to keep moving

Your instructor is wrong. Find another quickly before they do any more damage. You do not have to keep moving, and doing so when you are getting muddled over which way to steer or are going out of position is guaranteed to mess the manoeuvre up completely.

Can I fail for taking too long?

Yes, but you have to be really slow about it, or cause hold ups for other road users. I’ve only ever had one pupil fail for taking too long on a manoeuvre, and it was about 10 years ago on the parallel park. He reversed back and touched the kerb. He moved out to correct it, then touched the kerb again. He moved out one more time, and got it parked properly this time. The examiner failed him for taking too long because there was a car waiting.

What if I don’t have power steering?

It doesn’t matter. You need to steer enough – and that will be the same amount of steering that you’d use driving around the same sort of corner going forwards.

My last instructor told me to look out of the back (or side) window to follow the kerb

In my car – and many others – the rear sill is too high for this to work, and people who have been taught that way get into a terrible mess if they try it. I drive a Ford Focus, and many of those who pass their tests are likely to drive one, too. They were quite probably taught in a small “learner” car that there was never even the remotest possibility of them going out and buying (not until they reach 60 or 70, anyway).

The mirrors exist so that you can see what is behind you. Use them to follow the kerb and you’ll be able to reverse in any car. Having said that, if you can see the kerb out of the windows use that by all means – just remember that when you get your own car it may not work.

I can’t see the kerb when I reverse around the corner

If your mirrors are correctly set for normal driving then you WILL be able to see the kerb if you are carrying out the manoeuvre properly. If you’ve been taught to look out of the back or rear passenger windows, the chances are you’re driving a different car where that method won’t work.

What should I be looking for out of the back window?

Pedestrians and other road users – and not just out of the back windows. Keep a lookout all around as you carry out the manoeuvre.

What if I can’t see it’s clear?

You mustn’t reverse anywhere if you aren’t sure it is safe. If necessary, get out and have a look – but make sure the car is safely positioned and secured before you do.

When would a corner be unsuitable for this manoeuvre?

People ask this when they’re training to become ADIs because it’s one of the subjects that crops up at some point. The usual answer is when it’s a one-way street – you can’t reverse the wrong way up a one-way street. Other reasons for not reversing into a particular corner would be if it is very busy, if it is controlled by traffic lights, if it is within the boundaries/zigzags of a crossing, if it is on a dual carriageway (i.e. you’d be going the wrong way), on a motorway, if all-round visibility is restricted and there are a lot of people around, and so on.

Watch out for other drivers who might not care where they do it, or how they affect others. Taxi drivers, for example, will turn wherever and whenever they want – rules or no rules.

I can’t see the point of turn

If your mirrors are adjusted properly for normal driving you will be able to see the point of turn – it’s when the curved part of the kerb starts to move away from you in the left mirror. You don’t need to angle them down especially or anything, though some people do. However, if you’ve been taught to reverse by looking out of the rear windows then you will have problems in many vehicles.

Can you move forward to correct your position if you make a mistake?

Yes, but be careful. Having to add extra stages means having to do extra safety checks, and the pressure of knowing you’ve gone slightly wrong will increase the risk of you forgetting to do them. It’s best to get it right first time to avoid all of this. However, it isn’t a good idea to drive all the way back to the starting position so you can have a second try – apart from the additional safety checks, you’ll end up taking much longer over it and that can be grounds for failure.